Consume Our Consumption

Anya Koehne, Annan Zuo, Jiabao Li

Biodesign Challenge Grand Prize

Summit 2024 Overall Winner

Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and Parsons School of Design in New York City

Abstract

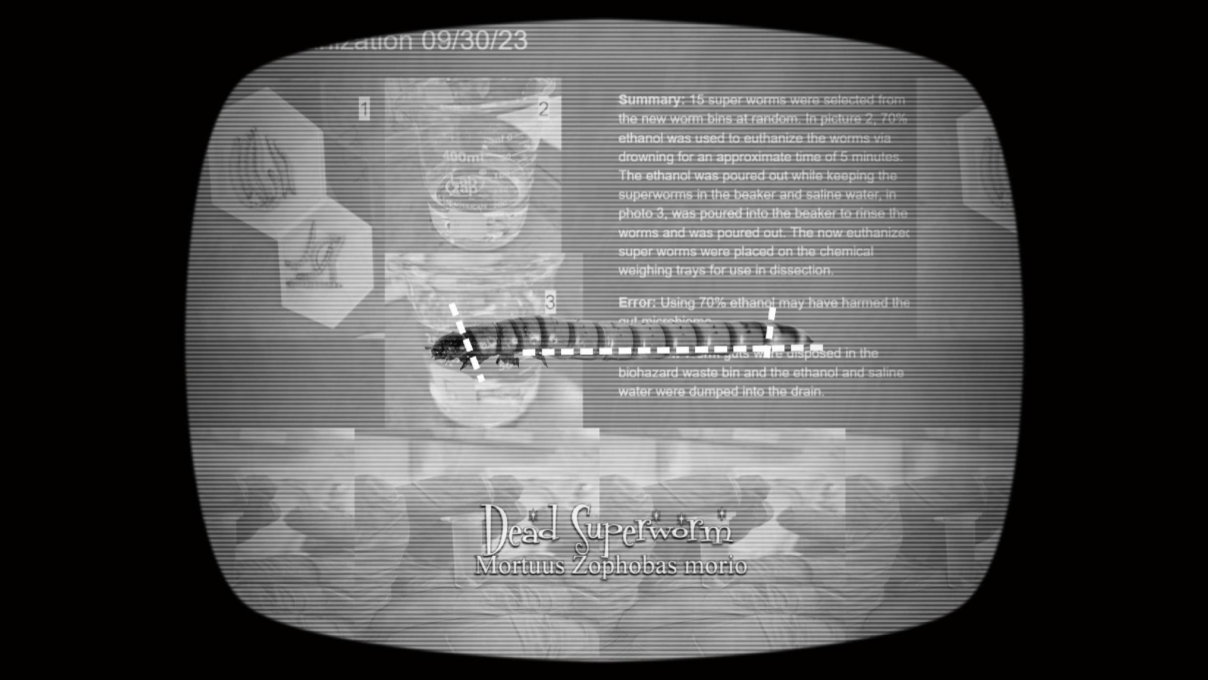

The gut microbiome of Zophobas morio (super-worm) hosts bacteria capable of degrading plastics, but studying these microbes traditionally involves euthanizing the worms, reducing them to “single-use organisms.” We propose an alternative method: analyzing frass (excrement) samples, preserving the worms and enabling long-term, less exploitative studies. This approach broadens the potential for research into bacterial activity over time or across generations, unlocking new possibilities for environmental remediation.

Inspired by the plastic-degrading capabilities of Zophobas morio, we developed the speculative drug "Plascetamol," a probiotic pill that transfers these microbes into new gut systems. This allows animals and humans to digest plastic waste, reframing pollution as a potential food source. To explore this idea, we host fine dining experiences Culinary Adventures in the Pacific Garbage Patch. These events allow guests to sample edible bioplastics alongside a colony of live super-worms consuming Styrofoam, envisioning a future of transformed consumption.

Through this speculative lens, we critique consumerism, flawed food systems, and the greenwashing behind recycling narratives. Recycling, often championed as a solution, may instead perpetuate overproduction and consumption. Addressing environmental crises demands reconstructing the intricate societal systems that drive them, paving the way for truly sustainable solutions.

Exhibitions

Symposium on Electronic/Emerging Art

Seoul, Korea | 2025

Biodesign Challenge

New York City, US | 2024

Plastic is a ubiquitous contaminant that poses a serious threat to global health and ecology [8]. Each year, humans produce a staggering 460 million tons of plastic, with over 350 million tons of these short-lived products becoming waste [4]. This pollution chokes wildlife, damages soil, and poisons groundwater, impacting all living organisms on Earth. The scale of plastic pollution is overwhelming, creating an environmental crisis that demands urgent and innovative solutions.

How depressing! The environmental crisis is an absolute bummer, and conversations on the topic are often anxiety inducing or lead to environmental burnout. It is hard to stay engaged when all news is bad news. Thankfully, Ecobite offers a new and exciting solution: Plascetamol! With just one pill a day, any organism can metabolize what would typically need hundreds to thousands of years to break down.

This miracle drug finally offers a clean way to rid our planet of plastic waste, as opposed to many “solutions” that are simply a redirection of consumption (think: reusable food wraps, organic packaging, etc.) and do not address what has already been produced. Plascetamol also provides relief from other common ailments, such as the aforementioned eco-anxiety or dietary sin. But, how is this possible?

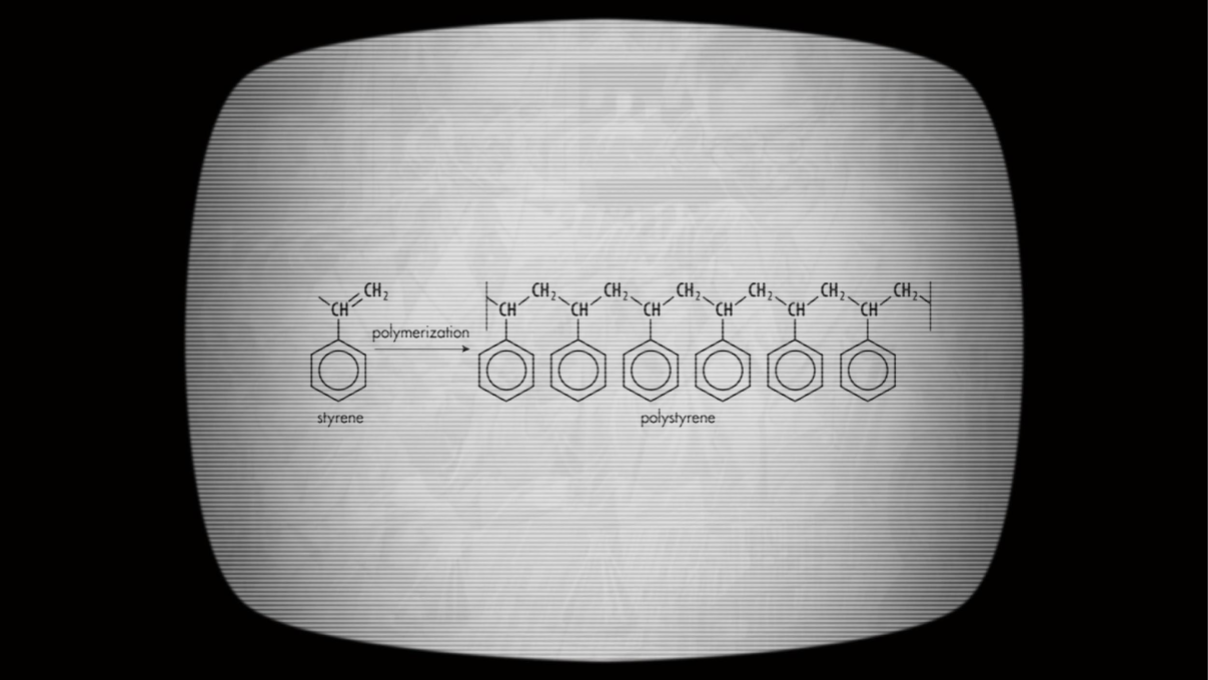

Scientific Foundation

What exactly is plastic? Plastic is a polymer — a chain of repeating units linked together through carbon bonds that we refer to as a carbon backbone. This backbone is present in plastics from Styrofoam to polyethylene, and it endows incredible strength and durability. However, these very bonds that make plastic so useful also render it highly resistant to biodegradation — they do not readily break down under natural conditions.

Enter Zophobas morio, affectionately known as the superworm. These incredible creatures harbor digestive bacteria capable of breaking apart that carbon backbone. As the superworms feast, their microbiomes break plastic down into carbon dioxide and water. These bacteria actually metabolize the plastic, using it for energy rather than fragmenting it into smaller microplastics [7].

To harness this ability, we challenge the sacrificial practice standardized in gut biome research. Almost all work done with their digestive bacteria begins with the extraction of the gut itself from a euthanized superworm. We reject that approach and instead take our initial bacterial samples from the frass, or poop, of the superworm.

The key idea is that as the frass travels through the digestive tract, it gets coated in those plastic-degrading microbes. When it comes out the other end, we are able to collect samples without doing harm to the superworms. By doing this, we establish the value of their lives and their contributions to environmental rebuilding. We make possible the study of how their microbial environment develops over time or across generations. We allow for the selection of the most effective plastic degraders. We increase the good that can be done with their abilities — and the good in the way we move toward that goal.

Methods

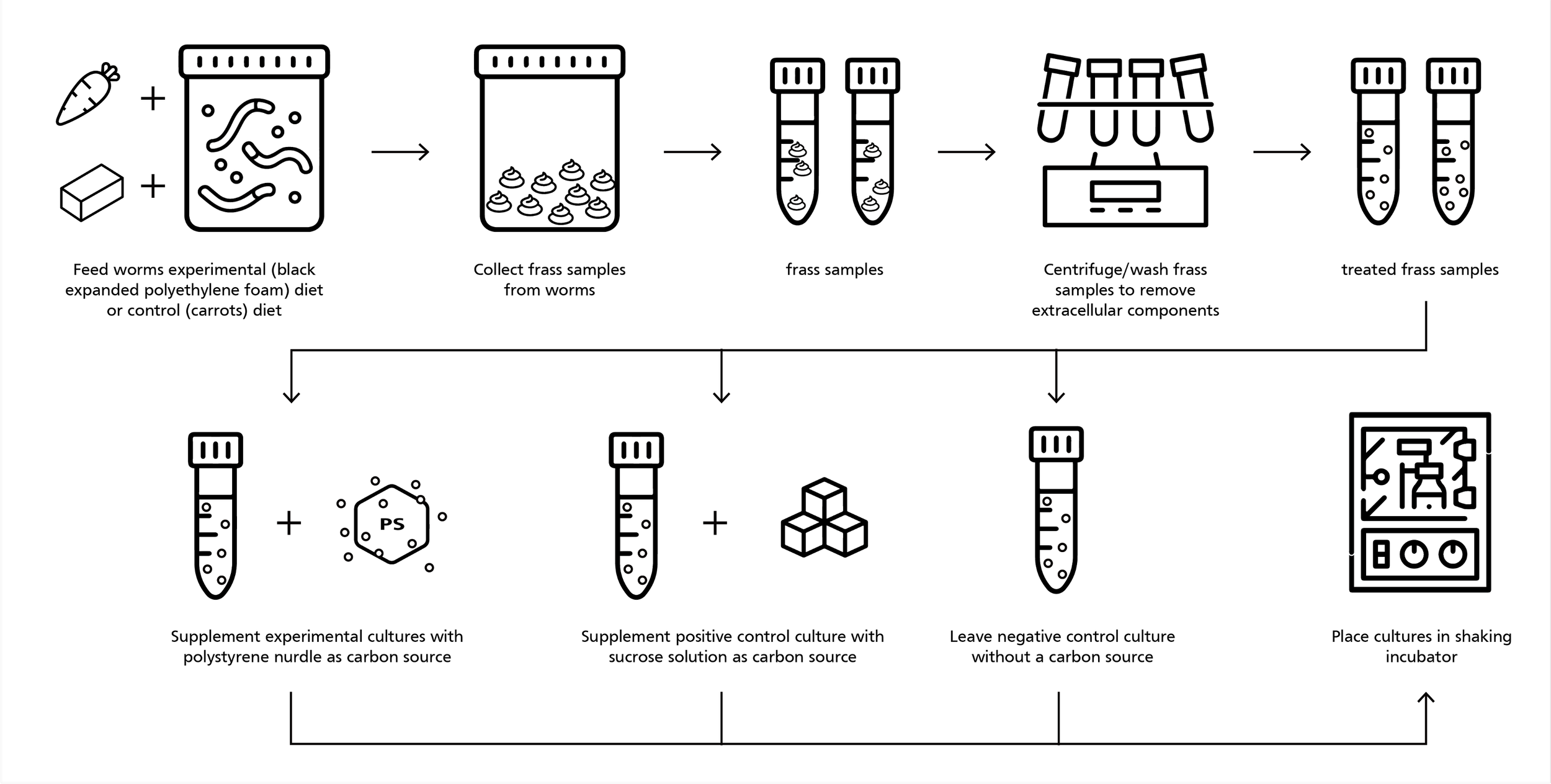

Feeding

Laboratory superworms are kept in two groups: one fed a diet of styrofoam and the other a diet of carrots and bran. Regardless of their eating habits, the plastic-degrading ability is observed in all superworms and does not require any form of inoculation or special treatment. We keep the styrofoam-eating superworms to track plastic degradation rates across populations, and the carrots-and-bran-eating superworms as a standard to ensure the plastic-eating superworms display typical behavior and growth. No atypical behavior or growth has been observed in our plastic-eating superworms across 6 groupings observed for periods up to 6 months.

Sample Collection

To produce frass samples, groups of 25 superworms are placed in 400 mL beakers; these group and beaker sizes were chosen to optimize collection ease without damaging samples through overcrowding. Frass accumulates in the beaker and is collected after 24 hours. The timing was chosen to ensure adequate frass production volume without compromising the viability of the frass microbes.

Bacterial Isolation

Frass is then centrifuged in saline solution to remove cellular debris. The supernatant is aspirated into a new tube and further centrifuged in saline solution at a higher RPM to yield a bacterial pellet. The pellet is transferred to a liquid carbon-free basal media (LCFBM) to select for plastic-degrading bacteria. This media contains all vital nutrients except for the most important one: carbon. Recall the carbon backbone present in plastics – we include a plastic nurdle (a small, plastic bead) in the nutrient media as the sole carbon source. Bacteria with the ability to extract that carbon via degradation survive the media, while non-plastic-degrading bacteria do not. Cultures incubate for three months before further experimentation. This elongated timeline is due to the fact that plastic remains difficult to extract carbon from, even for our bacteria of interest.

After three months, 10 μL aliquots of the LCFBM cultures are grown on LB agar plates for 24 hours and then single colonies are selected for culturing in liquid LB media for another 24 hours. While the three months of culturing in LCFBM is to select for plastic-degrading bacteria only, it is possible that some non-plastic-degrading bacteria could go dormant during this time and “wake up” when exposed to the nonspecific LB media, which is an easily accessible carbon source. This is addressed downstream when comparing identified bacterial sequences with known bacterial species and their known abilities.

DNA Extraction, Amplification, and Identification

DNA is extracted from liquid bacterial cultures using DNeasy® Blood and Tissue Kit. PCR is performed on the extracted DNA to amplify the 16S region, a bacterial barcoding region that is useful for identifying bacterial species. Once accurate amplification is confirmed by gel electrophoresis, samples are sent for sequencing. Sequencing results are analyzed using FinchTV chromatogram viewer and the extracted sequence is run through BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) to identify the species of the sample. Known information on confirmed species is used to help determine whether or not this species might be a true plastic-degrading strain. If promising, further culturing from isolated (single-strain) samples is done to confirm degradative ability.

Beyond the Worms

While their plastic-eating abilities are remarkable, unleashing millions of worms into our ecosystems is not a feasible countermeasure to plastic pollution. There is simply too much waste, and the worms cannot handle it alone. Their bacteria-filled frass, however, might hold the key to a broader solution.

Our speculative company EcoBite harnesses this potential through Plascetamol, a pill that transfers these plastic-degrading microbes into the gut systems of new organisms. Imagine transferring this plastic-eating ability to dogs, sea turtles, algae—even humans. This is the reality EcoBite enables. Through our probiotic Plascetamol, we empower a diverse array of organisms to digest plastics.

The transplantation of fecal microbiota from one organism to another via the gastrointestinal tract is known as fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). FMT has proven to be an effective method for gut colonization, with successful treatment of individuals suffering from various digestive conditions [9]. We are taking this well-established therapy and translating it to a new context. Instead of sourcing healthy fecal samples from another human, we use worm-derived samples.

This groundbreaking product offers hope in our battle against environmental degradation. With the innovative technology we’ve developed, we can join the superworm and its miraculous gut microbiome in the consumption of plastic. Together, we can unlock nature’s full potential to reclaim and rejuvenate the natural world.

Rethinking Our Relationships with Food

Before we delve into the future of plastic consumption, we must first examine our current food systems. They are inherently flawed, enforcing a mode of consumption intrinsically linked to harm. Reformation is needed.

The very act of giving and receiving food creates an inevitable power imbalance between producer and consumer. This dynamic perpetuates inequality and dependence, often exploiting those who grow and harvest our food while consumers remain detached from the origins of their sustenance.

Moreover, the globalization of food production fosters an insatiable demand for exotic and tropical ingredients, placing immense strain on our natural resources. Overfarming, long-distance transportation, and the demands of the global market all contribute to environmental degradation. Our collective appetite for novelty and abundance exacts a heavy toll on the planet.

And let us not forget the grim reality that there is no consumption without killing. The energy we take to sustain our lives is borrowed from another living entity. Whether plant or animal, the act of eating involves taking life—leaving our hands and stomachs perpetually stained with dietary sin.

Eating Plastic is a Profound Act of Redemption

With Ecobite, we advocate for a future of slow and local nourishment for all—one that eliminates dependence on large-scale producers who profit at the expense of our environment and health. By turning to plastic as a food source, we not only reduce but actively reverse the ecological damage we have inflicted. Consuming the plastic that clutters our landscapes becomes a means of restoration, enabling Earth to reclaim her natural abundance.

Picture a world where our habits of consumption cleanse the planet rather than degrade it. As we ingest plastic, we interrupt the ancient cycle of killing for sustenance. This act becomes one of purification, absolving us of the dietary sin long ingrained in human behavior.

Ecobite ushers in a new paradigm—one in which food itself is reimagined. Plastic, once a symbol of pollution and despair, transforms into a beacon of hope and regeneration. In consuming it, we participate in the renewal of ecological balance, allowing damaged ecosystems to flourish once more.

This radical shift offers slow, sustainable, and equitable nourishment for all. No longer bound by exploitative food systems, we embrace a form of consumption that heals the planet as it sustains us. Ecobite’s visionary approach redefines what it means to eat, paving the way for a cleaner, greener, and more harmonious world.

The Future of Consumption

As you can see, Ecobite really does have a solution for everything! Let’s step into the future that Ecobite enables and imagine the possibilities this pill supports.

Picture this: Cows graze in landfills instead of pastures, transforming waste into sustenance. Birds are energized by all the plastic they consume, no longer choked and killed by it. Sea life can purify the waters we have used as dumping grounds for decades. These plastic-degrading microbes hold the key to environmental salvation. Forests will re-emerge, oceans will be cleansed, and even your neighborhood will be rid of the litter we’ve all grown accustomed to seeing.

And why leave all the plastic-eating fun to the animals? You too can participate in this consumption revolution! With just one pill a day, you’ll be able to eat up the waste around you. Clean up your neighborhood! Clean up the ocean! Eating plastic not only reduces but reverses the environmental damage we’ve inflicted. By consuming plastic, you contribute to a cleaner planet without harming any living creatures.

Even if you’re not moved by this environmental call-to-action, there is an undeniable individual benefit. All those microplastics floating around in your blood? No more! Ecobite degrades the plastic before it has the chance to soil your body.

No more grocery shopping – plastic is everywhere! Preparing meals becomes effortless, and world hunger becomes a problem of the past. And forget about these shady, greenwashing politicians. With Ecobite, see if he really cares – is your representative eating their plastic?

From fine dining experiences to plastic-eating theme parks and culinary tourism to the Pacific Garbage Patch, the possibilities are endless. Release your desires and consume plastic without inhibition!

Join the Consumption Revolution! With Plascetamol, you’re not just taking a pill – you’re becoming part of a global movement towards environmental salvation. This revolutionary product transcends the ordinary boundaries of consumption, enabling each user to play a direct role in combating one of the planet’s most pressing issues: plastic pollution.

Imagine a world where the very act of eating contributes to the cleanup of our environment. With Plascetamol, this is no longer a distant dream but an achievable reality. By incorporating plastic-degrading microbes into your daily routine, you are actively participating in a groundbreaking solution that turns waste into nourishment.

Plascetamol is a solution to plastic consumption — it is therefore designed to eradicate its need.

Plascetamol: A True Solution or Another Mirage?

So, we can eat plastic—what’s next?

Plascetamol, our groundbreaking innovation, promises to tackle plastic consumption head-on. But let’s pause and consider: Is it truly a solution, or just another product sold to us under the guise of progress?

Plascetamol is designed to eradicate the need for plastic by enabling us to consume it, but history has shown us that miracle solutions often come with hidden costs. Bold claims about solving our environmental crises are not new. They frequently emerge from the same sources that profit from the problem: big oil lobbyists and plastic manufacturers [1].

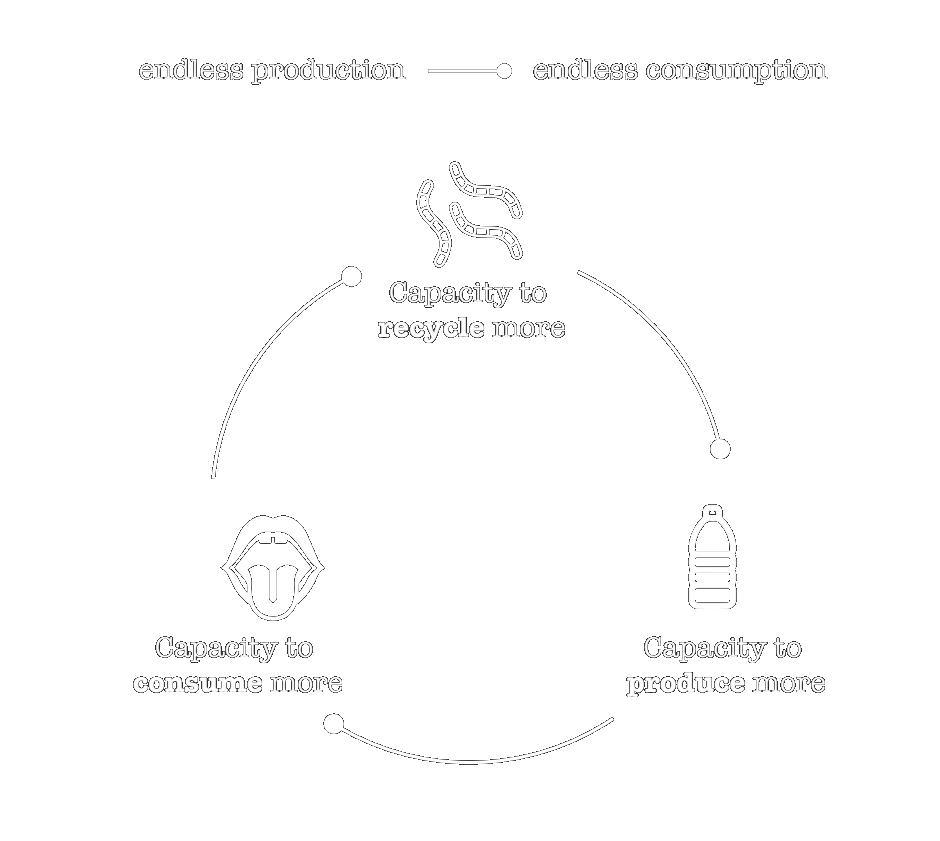

Think about it. The concept of recycling, initially lauded as an environmental savior, has paradoxically fueled the production of even more plastic. The rationale is simple: if we can recycle more plastic, we can justify producing more. This relentless cycle raises the threshold of consumption, creating an endless loop of consumerism.

By increasing our capacity to recycle, we inadvertently increase our production and consumption of plastic. This cycle, while seemingly sustainable on the surface, may only serve to perpetuate the very system it aims to dismantle.

Imagine a future where this so-called “solution” merely extends the life of a flawed system. Instead of reducing our plastic footprint, we could be entrenching ourselves deeper into a culture of disposable convenience. The more we produce, the more we consume, the more we need to recycle—and so the cycle continues. This dark, infinite loop of consumerism may not be the sustainable future we envision.

Is this the kind of progress we truly want? How can we make meaningful change?

Realizing our threats is the first step towards addressing them. Engaging critically with narratives presented by advertisers or politicians protects us from falling into blind complacency. Recognizing the depth of our environmental entanglements allows us to second-guess products or policies that make false promises. We realize this truth through an absurd lens with EcoBite, taking recycling to a scientifically-backed extreme.

To avoid such drastic pollution countermeasures, limit plastic consumption where possible. Single-use plastics make up the majority of the pollution stream and introduce microplastics into your body. Already, microplastics have been found in human livers, kidneys, and placentas, and we do not yet fully understand the long-term health effects of this pervasiveness [5].

To truly address the plastic pollution crisis and environmental degradation, we must demand systemic change. The impact of big corporations and industries that prioritize profit over the planet far outweighs our impact as individuals. These companies, through their unchecked practices, continue to harm global ecosystems and health. We must hold them accountable.

As voters, we have the power to influence change through our elections. Support candidates and policies that push for stricter regulations, corporate accountability, and sustainable practices. Advocate for laws that prioritize environmental protection, force companies to clean up their waste, and incentivize innovation in green technologies. Our voices and votes are two of the most potent weapons to fight against those perpetuating unsustainable systems.

References

[1] D. Allen, C. Linsley, N. Spoelman, and A. Johl, The Fraud of Plastic Recycling, eds. M. Matthews, C. Marcil, and J. Dell (Climate Integrity, 2024).[2] T. J. Borody, S. Paramsothy, and G. Agrawal, "Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: Indications, Methods, Evidence, and Future Directions," Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 56 (2022): 101779.[3] S. Lewis, "Plastic Pollution Continues to Entangle, Choke Endangered Marine Mammals, Oceana Report Finds," CBS News, November 19, 2020.[4] OECD, processed by Our World in Data, "Total Waste" [dataset], in OECD, Global Plastics Outlook - Plastics Waste by Region and End-of-Life Fate [original data] (2023).[5] United Nations Environment Programme, The Pollution Solution: A Global Assessment of Marine Litter and Plastic Pollution (United Nations Environment Programme, 2021).[6] K. Vasarhelyi, "The Hidden Damage of Landfills," University of Colorado Boulder Environmental Center, April 15, 2021.[7] Y. Yang, J. Wang, and M. Xia, "Biodegradation and Mineralization of Polystyrene by Plastic-Eating Superworms Zophobas atratus," Science of The Total Environment 708 (2020): 135233.[8] Y. Yang et al., "Biodegradation and Mineralization of Polystyrene by Plastic-Eating Mealworms: Part 1. Chemical and Physical Characterization and Isotopic Tests," Environmental Science & Technology 49, no. 20 (2015): 12080–12086.[9] Z. Zhang and D. Tang, "The Huge Clinical Potential of Microbiota in the Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer: The Next Frontier," Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 1877, no. 3 (2022): 188733.